Berat County

| Berat County Qarku i Beratit |

|

|---|---|

| — County — | |

|

|

|

|

| Country | |

| Number of Districts | 3 |

| Capital | Berat |

| Area | |

| - Total | 1,798 km2 (694.2 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 455 m (1,493 ft) |

| Population (January 1, 2010)[1] | |

| - Total | 170,845 |

| - Density | 95/km2 (246.1/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) |

| - Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) |

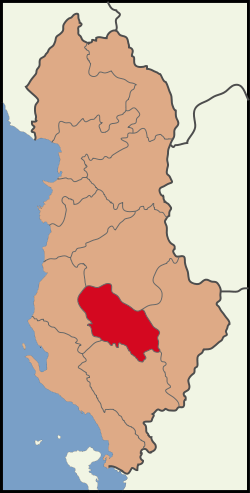

| Capital - Berat City | |

The County of Berat (Albanian: Qarku i Beratit) is one of the 12 counties of Albania. It consists of the districts Berat, Kuçovë, and Skrapar; its capital is Berat. Berat is a UNESCO World Heritage Site (inscribed in 2005 under criteria iii and iv) covering an area of 58.9 hectares (146 acres) and a buffer zone of 136.2 hectares (337 acres). It lies 123 km south of Tirana, the capital of Albania.[2][3][4][5]

The historical, cultural and architectural heritage of the Byzantine era and of the Ottoman Empire is amply represented in the many monuments still well preserved and maintained in the Berat city of the county. It is popularly known as the "City of a Thousand Steps" and also a "Museum City."[4]

Contents |

History

Antipatrea (Greek: Αντιπάτρεια) was an ancient Greek polis in the region of Epirus, now Berat. It was founded by Cassander as Antipatreia, who named it after his father Antipater at 314 BC.[6]. An ancient Greek fortress and settlement are still visible today.[7] Dassaretae tribe existed in the area,[8] as early as the 6th century BC. It was captured by the Romans in the 2nd century BC. Livy (31.27.2) describes Antipatrea as a strongly fortified city in a narrow pass that the Romans sacked and burned. The city was composed of two fortifications on both banks of the Osum River.[4]

Historical manuscripts such as the 6th century Codex Purpureus Beratinus, discovered in 1868, and the Codex Aureus, a 9th century Greek language manuscript have revealed much about the history of the region and that Berat had a reputation for producing manuscripts; 76 of the 100 codes protected in the National Archives of Albania are from Berat, indicating its historical importance.[4][9]

The town of Berat became part of the unstable frontier of the Byzantine Empire following the fall of the Roman Empire and, along with much of the rest of the Balkan peninsula, it suffered from repeated invasions by Slavs and other tribes. During the Byzantine period, it was known as Pulcheriopolis.[4]

The Bulgarians under Simeon I captured the town in the 9th century and renamed it "Beligrad" (White City). They were eventually driven out in the 11th century. During the 13th century, it fell to Michael I Ducas, the ruler of the Despotate of Epirus.[4]

In the latter part of the 13th century Berat again came under the control of the Byzantine Empire. In 1280–1281, the Sicilian forces under Hugh the Red of Sully laid siege to Berat. In March 1281, a relief force from Constantinople under the command of Michael Tarchaneiotes was able to drive off the besieging Sicilian army.[10] In 1335-1337, Albanian tribes descended and for the first time reached the area of Berat,[11][12] while in 1345 the town passed to the Serbs.[4]

The Ottoman Empire conquered it in 1450 after the siege of Berat and retained it until 1912. However, Ali Pasha (b.1744- d.1822), an Albanian chief, took control of Berat through deceitful tactics, trickery, bribery and bold political moves and was eventually recognized by the rulers in Istanbul. He refortified the city in 1809.[4][13] In 1867, Berat became a sanjak in the Janina (Yanya) vilayet. During Ottoman rule, it was known Arnavut Belgradı in Turkish at first, and then Berat.

During the early period of Ottoman rule, Berat fell into severe decline. By the end of the 16th century it had only 710 houses. However, it began to recover by the 17th century and became a major craft centre in the Ottoman Balkans, specializing in wood carving. During the 19th century, Berat played an important part in the Albanian national revival.[4] It became a major base of support for the League of Prizren, the late 19th century Albanian nationalist alliance. In November 1944, the communist-controlled Anti-Fascist National Liberation Council of Albania declared in Berat that it was the provisional government of the country, signalling the beginning of the Enver Hoxha dictatorship.[4]

Geography

Alone among the counties of Albania, Berat neither borders the sea nor another country. It is bounded by Elbasan County to the north, Korçë County to the east, Gjirokastër County to the south and Fier County to the west. The biggest river is the Osum which flows through the town of Berat itself and joins the Molisht River. Berat is bounded by Tomorr (known as "Mount Olympus" or "the throne of gods "[5](2,416 metres (7,927 ft)), and Shpirag (1,218 metres (3,996 ft) high) mountains, which are covered with rich pine forests. A deep ravine cut by the Osum River on its west side, which is 915 metres (3,002 ft) deep in lime stone rock formation is where the Berat city is situated on stepped terraces. Other rivers include the Çorovoda River which passes through the town of Çorovodë home to the canyon known as "Pirogosh".[4][14]

|

||

|

Left: Shpiragu Mountain. Right: Tomorr Mountain

|

||

The geographical formations of the region are frequently mentioned in local folklore. According to legend, Tomorr Mountain personified a giant who fought his brother Shpirag or Shpiragu, personified by a nearby mountain, for the love of a young woman.[9] The two brothers fought bitterly for her affections and ended up killing each other. Deep in sorrow, the legend states, the grieving woman for whom they had contested wept over their deaths; her tears created the Osum River.[4][9][15] She was then said to have turned to stone, becoming the foundation on which Berat Castle is now built.[9] Both Tomorr and Shpirag mountains are visible from Berat.

The climate in the region is generally Mediterranean, but varies by local topography. There are diverse microclimates in the county, including Alpine.[14] Summers are dry while heavy rains are experienced during the winter. Climate conditions near Berat are conducive to farming and related agricultural industries.[14]

Administrative divisions

| District | Capital | District Population (2010)[16] |

Area (km²) | Municipalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berat District | Berat | 117,066 | 939 | Berat, Cukalat, Kutalli, Lumas, Otllak, Poshnjë, Roshnik, Sinjë, Tërpan, Ura Vajgurore, Velabisht, Vërtop. |

| Kuçovë District | Kuçovë | 34,907 | 84 | Kozare, Kuçovë, Perondi. |

| Skrapar District | Çorovodë | 18,872 | 775 | Bogovë, Çepan, Çorovodë, Gjerbës, Leshnjë, Poliçan, Potom, Qendër, Vëndreshë, Zhepë. |

Landmarks

The coexistence of various religious and cultural communities over several centuries, beginning in the 4th century BC into the 18th century is apparent in Berat. The town also bears testimony to the architectural excellence of traditional Balkan housing construction, which date to the late 18th and the 19th centuries. Some of the landmarks of that historical period could be seen in the Berat castle, Churches of the Byzantine era such as the Church of St. Mary of Blaherna (13th century), the Bachelors' Mosque, the National Ethnographic Museum, the Sultan's Mosque (built between 1481 and 1512), Leaden Mosque (built in 1555) and the Gorica Bridge.[3][9][17][18]

Berat Castle

Berat Castle, is located inside of the city. The castle and its 24 towers were built on a rocky hill on the left bank of the Osum, on the area of some 5.11 hectares (12.6 acres)[9], and is accessible only from the south. After being burned down by the Romans in 200 BC,[4][19] the walls were strengthened in the fifth century under Byzantine Emperor Theodosius II, and were rebuilt during the 6th century under the Emperor Justinian I and again in the 13th century under the Despot of Epirus, Michael Angelus Comnenus, cousin of the Byzantine Emperor.[3][4]

The main entrance, on the north side, is defended by a fortified courtyard and there are three smaller entrances. Though considerably damaged, the fortress of Berat remains a major cultural and tourist site of the city. The surface that it encompasses made it possible to house a considerable portion of the city's inhabitants. The buildings inside the fortress were built during the 13th century and because of their unique architecture are preserved as protected cultural monuments. The population of the fortress was Christian, and had about 20 churches (most built during the 13th century) and only one mosque, for the use of the Turkish garrison, (of which there survives only a few ruins and the base of the minaret). The churches of the fortress were damaged through years and only some have remained. The castle library contains a number of important manuscripts.[3][9]

National Ethnographic Museum

|

|

|

|

Left: House. Right: Local old men.

|

||

Berat National Ethnographic Museum opened in 1979.[17] It contains a diversity of everyday objects from throughout Berat's history. The museum contains non-movable furniture which hole a number of household objects, wooden case, wall-closets, as well as chimneys and a well. Near the well is an olive press, wool press and many large ceramic dishes, revealing a glimpse of the historical domestic culture of Berat's citizens.[17] The ground floor has a hall with a model of a medieval street with traditional shops on both sides and on the second floor is an archive, loom, village sitting room, kitchen and sitting room.[3][4][18]

Gorica Bridge

Gorica Bridge, which connects two parts of Berat was originally built from wood in 1780, but was later rebuilt with stone in the 1920s.[9] The 7 arch bridge is 129 metres (423 ft) long and 5.3 metres (17 ft) wide and is built about 10 metres (33 ft) above the average water level.[9] According to local legend, the original wooden bridge contained a dungeon in which a girl would be incarcerated and starved to appease the spirits responsible for the safety of the bridge.[3][9]

Religion and culture

|

|

|

|

Left: New Orthodox Cathedral of Berat. Right: Leaded Mosque of Berat

|

||

The main religions practiced in Berat County are Orthodox Christianity and Islam. The landscape of a mixture of minarets of mosques and grand Orthodox churches and chapels are a testament to the religious coexistence of Berat inhabitants.[3] Berat was the seat of a Greek Orthodox Bishpric in medieval and modern times, and today Aromanian and even Greek speakers can be found in the city and some surrounding villages.[20] Recently Berat was added to UNESCO’s World Heritage list as an example of the co-existence of religions and cultures. [21]

The landscape of a mixture of minarets of mosques and grand Orthodox churches and chapels are a testament to the religious coexistence of Berat inhabitants.[3] The Church of St. Mary of Blaherna in Berat dates to the 13th century, and contains 16th century mural paintings by Nikola, son of the Albania's most famous medieval painter, Onufri. The first inscription recording Onufri's name was found in 1951, in the Shelqan church. The Kastoria church dates to 23 July 1547 and a reference to Onufri's origin : I am Onufri, and come from the town of Berat. Onufri's style in painting was inherited by his son, Nikola (Nicholas), though not so successful as his father. Onufri's museum contains works of Onufri, his son, Nikola and other painters. There is also a number of icons and some fine examples of religious silversmith's work (sacred vessels, icon casings, covers of Gospel books, etc.). Berat Gospels, which date from the 4th century, are copies (the originals are preserved in the National Archives in Tirana). The church itself has a magnificent iconostasis of carved wood, with two very fine icons of Christ and the Virgin Mary. The bishop's throne and pulpit are also of considerable quality.[3][4]

Near the street which descends from the fortress is the Bachelors' Mosque (Albanian: Xhami e Beqareve), built in 1827. It has an attractive portico and an interesting external decoration of flowers, plants, and houses. The Sultan's Mosque (Albanian: Xhamia e Mbretit), the oldest in the town built in the reign of Bayazid II (1481–1512), is notable for its fine ceiling. The Lead Mosque (Albanian: Xhamia e Plumbit), built in 1555 and so called from the covering of its cupola. This mosque is the centre of the town. The Tekke of the Helveti (Teqe e Helvetive), of 1790, with a porch and a carved and gilded ceiling. Near of tekke is purported to be the grave of Shabbatai Zevi, a Turkish Jew who had been banished to Dulcigno (present day Ulcinj) who created controversy among his followers upon his conversion to Islam.[3][4]

Folk music culture exists in Berat County and the performers often wear traditional dress.[4]

References

- ↑ "POPULLSIA SIPAS PREFEKTURAVE, 2001-2010". Albanian Institute of Statistics. http://www.instat.gov.al/graphics/doc/tabelat/Treguesit%20Sociale/Popullsia/POP%202009/t4%20.xls. Retrieved 2010-09-09.

- ↑ 2006 census

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 "UNESCO.orgHistoric Centres of Berat and Gjirokastra". Unesco.org. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/569. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 "Berat". Albanian Canadian League Information Service. http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:cBtwwAmP6O4J:albca.com/albania/berat.html+Folk+art+in+Berat+county&cd=3&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=in. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Albanian Tourist Information" (pdf). Republic of Albania. http://akt.gov.al/tinymce/jscripts/tiny_mce/plugins/filemanager/files/broshura_ture_harte/informacion.pdf. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- ↑ Epirus: the geography, the ancient remains, the history and topography of ... by Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond,"founded Antipatreia in Illyria at c. 314 BC"

- ↑ The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 6: The Fourth Century BC by D. M. Lewis (Editor), John Boardman (Editor), Simon Hornblower (Editor), M. Ostwald (Editor), 1994, ISBN 0-521-23348-8, page 423, "These Dassareti not to be confused with the Greek speaking Dexari or Dessaretae of the ,"

- ↑ The Illyrians by John Wilkes,page 98,"the Dassaretae possessed several towns...Chrysondym, Gertous or Gerous..."

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 "The Castle". Castle Park. http://www.castle-park.com/berat_city.htm. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ↑ Norwich, John Julius. The Decline and Fall of the Byzantine Empire. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996) p. 246-247

- ↑ Steven G. Ellis, Lud'a Klusáková. Imagining frontiers, contesting identities. Edizioni Plus, 2007 ISBN 978-88-8492-466-7, p. 134 "In 1337 the Albanians of Epirus Nova invaded the area of Berat and appeared for the first time in Epirus".

- ↑ Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond. Migrations and invasions in Greece and adjacent areas. Noyes Press, 1976, ISBN 978-0-8155-5047-1, p. 61 "By 1335 they were in possession also of the area between Berat and the Gulf of Valona"

- ↑ The New American encyclopaedia: a popular dictionary of general ..., Volume 1. D. Appleton. 1865. p. 354. http://books.google.com/books?id=--VDAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA354. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "Eonomic Development of the City of Berat". Agenda Institute. http://www.agendainstitute.org/img/foto/agenda_SWOT_analysis_Berati_en.pdf. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- ↑ A dictionary of Albanian religion, mythology and folk culture, Robert Elsie, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2001, ISBN 1-85065-570-7, p. 253.

- ↑ "POPULLSIA SIPAS RRETHEVE, 2001-2010". Albanian Institute of Statistics. http://www.instat.gov.al/graphics/doc/tabelat/Treguesit%20Sociale/Popullsia/POP%202009/t2.xls. Retrieved 2010-09-09.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Ethnographic Museum". Berat Museum. http://www.beratmuseum.net/index_etno_en.htm. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "National Ethnographic Museum, Berat". Albania Shqiperia. http://albania.shqiperia.com/kat/m/shfaqart/aid/2243/National-Ethnographic-Museum-Berat.html. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ↑ "Berat". Albanian Heritage. http://www.albanianheritage.net/docs/berati%20gri%20edward%20lear.pdf. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ↑ Winnifrith Tom. Badlands, borderlands: a history of Northern Epirus/Southern Albania. Duckworth, 2002, ISBN 978-0-7156-3201-7, p. 29.

- ↑ Berat as an example of the co-existence of religions and cultures (Albanian)

See also

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||